By @paulnewnham

“I’m hungry…” is a phrase I hear frequently when raising four active kids. Quite often between lunch and dinner they want a whole other meal. Then, as they stand with the fridge or cupboard wide open, staring into choices of food ready to be consumed, I hear, “There’s nothing to eat!”

This is not real, true hunger. It’s a learned behaviour after living such a privileged life. They are hungry in their understanding of ‘I want food’, but it is a completely different concept of real ‘hunger’ as felt by over 800 million people who go to bed truly hungry each night. True hunger equates to malnutrition, whereby a person does not consume enough nutrients to lead a healthy life.

After a prolonged and steady decline, 2017 is the first year in a decade that there has been a rise in the number of hungry people. At the same time, there has been a continued aggressive rise in obesity. On the surface, this seems to be a highly unusual global phenomenon – an increase in global hungry with a simultaneous increase in global obesity. It begs the question: are the two related?

Statistically, there are approximately two obese people for every one hungry person. Malnutrition in all of its forms- undernutrition, micronutrient deficiencies and overweight/obesity- is increasing. The recently released Global Nutrition Report 2017 showed that 88% of countries face a serious burden of either two or three forms of malnutrition namely undernutrition, micronutrient deficiency or overweight/ obesity. There is also now evidence which suggests that people who experience undernutrition as children are more likely to be overweight as adults. This double and even triple burden is making the work towards achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) even more challenging.

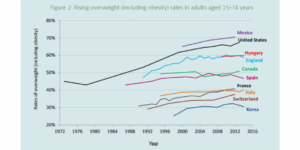

Mexico is an example of a country that has both persistent hunger and over consumption of the wrong type of food. Currently, Mexico is plagued by problems of malnutrition, anaemia, and obesity according to the 2017 Global Nutrition report. Though acute malnutrition has dropped significantly, the FAO estimates 5.4 million people to be undernourished. In addition, one in four children are overweight or obese, and that number increases to one in three for teenagers. Nationally, over 32.4% of adults are obese and 70% of adults are overweight in Mexico according to OECD 2017 Report. The proportion of obese adults is expected to increase to 40% by 2030 (OECD 2017 report) with the problem being more prevalent in urban populations.

The above graph is sourced from the Obesity Update 2017 report by OECD.

This begs the questions: Why do we see this change when hunger has been on the decline until last year? Why is there a concurrent rise in people eating too much, and the wrong types of foods?

Our planet produces more than enough food to feed everyone and has for a number of years. However, food is unequally distributed and far too much is wasted. Some have access to much, while others not enough. The increased production of cheaper, produced food has made food more accessible to those that would otherwise be without as well as resulted in people consuming the wrong type of food. These foods, while not bad in and of themselves as occasional foods, are often higher in salt, sugar and saturated fats, while their nutrition content is questionable.

The attractiveness of these foods is understandable for both consumer and producer. For the consumer, processed foods are often cheaper and thus are more accessible and affordable. They have longer shelf lives and are boxed in ready-to-eat portions with disposable packaging. Mass producers are able to create large quantities of these products at minimal cost to themselves, squeeze margins and generate attractive marketing, all of which increases overall profits exponentially. This has led to the aggressive expansion of processed foods into new markets in Latin America, Asia and Africa. While in some places this phenomenon, coupled with globalisation, has resulted in a positive reduction in the numbers of hungry or malnourished people, it has also contributed to an equitable jump in the number of overweight and obese children. This increase has been significant and fast.

Simultaneously, increased urbanisation – the shift away from living in rural areas, to the lure of cities – has resulted in less active forms of work and play. Increasingly sedentary lifestyles, together with significant cultural shifts in consumption patterns – from locally grown, seasonal produce to highly processed, long-life products – has had profound and wide-reaching effects. Companies have tried to respond to this phenomenon by offering low salt and sugar options and advertising serving sizes but on the whole, this has been too little to halt the overall impacts.

As a parent myself, with four growing children living in the UK, this is a major concern for me. It is so convenient and affordable to fill my kids up with processed foods that they love to inhale, rather than take the extra moments to prepare local produce. Having seen first-hand the effects globally of a poor diet and understanding some of the science around nutrition, we are actively trying to raise children that understand what a balanced diet is. Eat seasonally, eat locally, and eat food that looks the same as when it was grown or harvested. Prepare food from scratch in the kitchen. Know and understand what each ingredient is. Also, and most importantly, only consume what you need, not necessarily what you might want. This task is becoming harder and harder.

This paradox is not easily addressed but the future health of our planet and its population is at stake. Changes need to be carried out from the household level to the production level and involve all of the supply chains in between. The current existence of double and triple burdens of malnutrition in countries, calls for integrated action that tackles malnutrition in all its forms: from the causes of obesity to the causes of wasting and stunting. It requires all countries to evaluate and restructure their food systems in their entirety. Laws around food marketing, educating consumers, and ethical food supply chains, are just a few of the areas that must become active advocates in the food discussion, in order to build a sustainable, equitable food future for everyone.

This is just one of many paradoxes within our food system. Now more than ever we need to engage people more intentionally to effect change. The Food Sustainability Media Award is looking to showcase excellence in telling this story.