Co-authored by the five UN agencies IFAD, WFP, WHO, FAO and UNICEF, the newly released State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World (SOFI) Report is an important stocktake of global progress to achieve SDG2.1: Zero Hunger and SDG2.2: End all forms of malnutrition.

The 2024 report warns that we are off track to end hunger and malnutrition in the six remaining years to the 2030 SDG deadline. And, ahead of the 2025 Financing for Development Summit, the report calls for both an increase and a more efficient use of existing financing for food security and nutrition, particularly for countries facing significant difficulty in accessing financing.

Below we preview the report’s key findings through five numbers. Access the full SOFI 2024 report here.

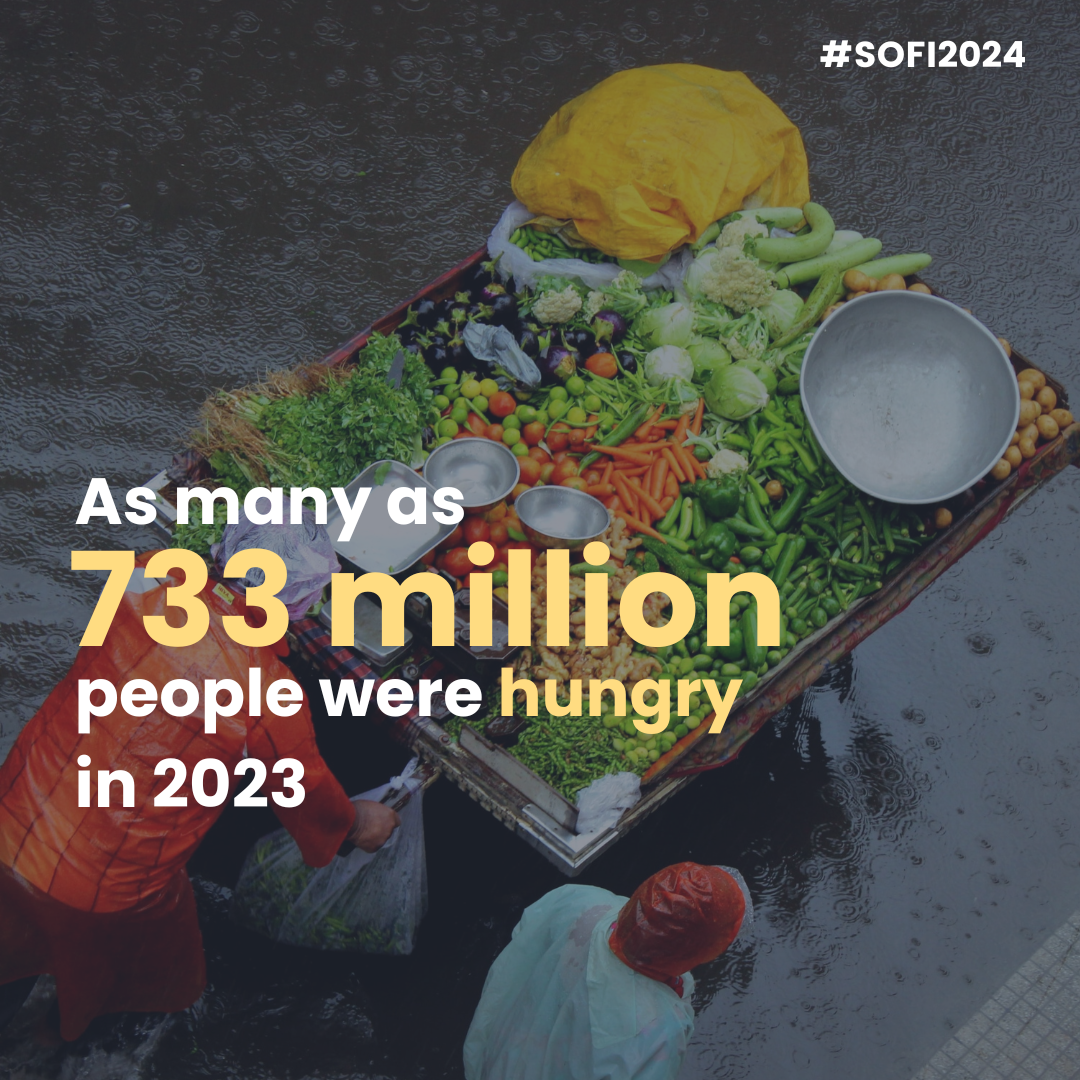

733 million people went to bed hungry in 2023. Similar to the 2021 and 2022 statistics, this figure shows little progress has been made in tackling global hunger, which the report attributes to the impacts of high food prices, climate change, conflict and economic reverberations from the COVID-19 pandemic.

This global number can be broken down regionally: hunger is still increasing in Africa where one in five people are hungry, compared to the world average of one in 11 people hungry. Rates of hunger have remained unchanged in Asia (where 8.1% of the population is hungry) while hunger is on the decline in Latin America (6.2% of its population is hungry). These regional figures hide sub-regional disparities where, for example, the percentage of the population that goes hungry in the Caribbean is more than three times that of Latin America.

On this trajectory, an estimated 582 million people (or 6.84% of the world’s population) will be hungry at the deadline of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in 2030. The majority of these people are predicted to live in Africa (308.1 million), compared to Asia (229.1 million) and Latin America and the Caribbean (33.7 million).

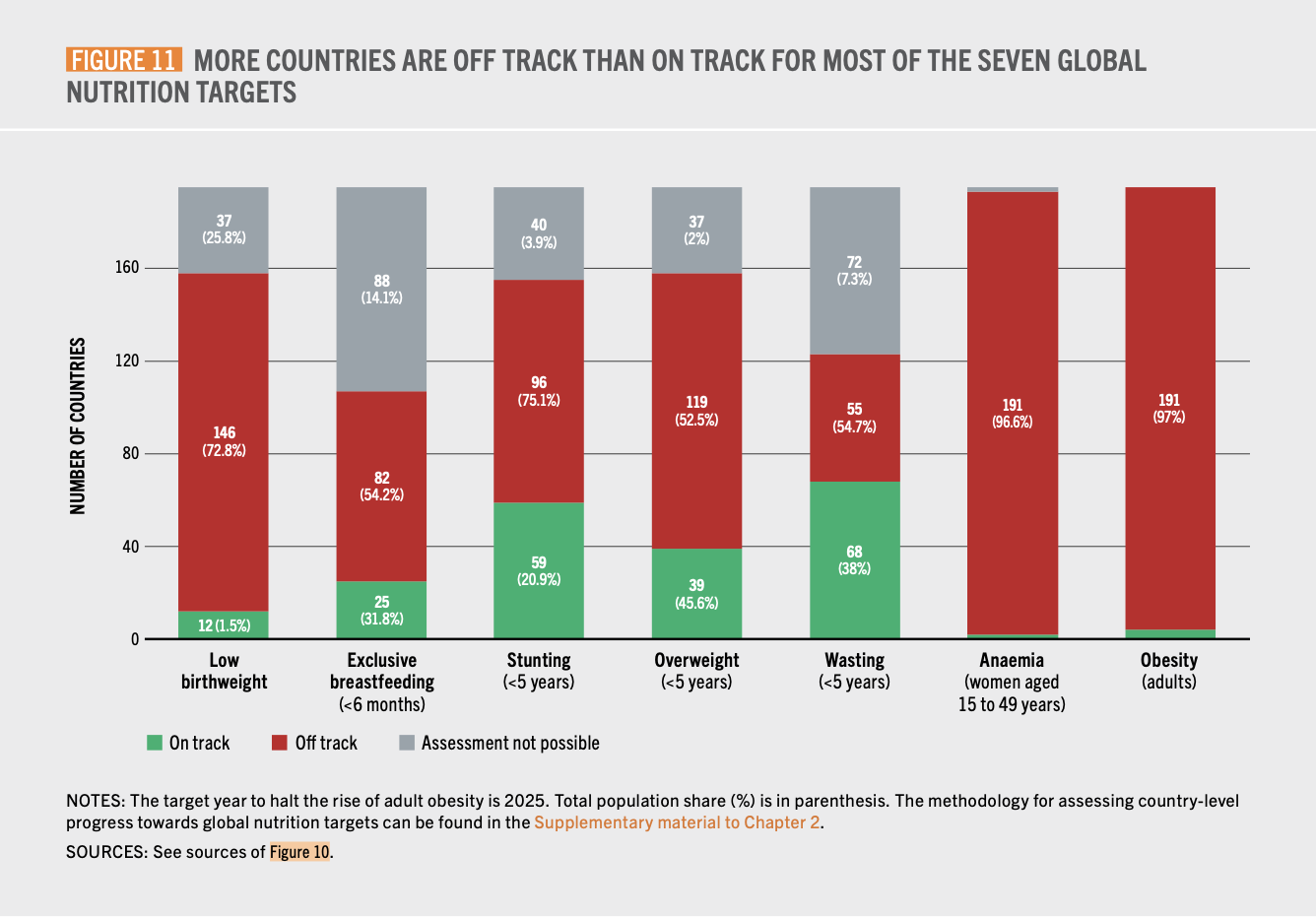

An estimated 19.5% of all children under five will be stunted at the 2030 deadline. This is indicative of global trends towards the global nutrition targets – the world is off track to achieve any of the seven global nutrition targets identified by the World Health Assembly or SDGs by 2030.

Little progress has been made in tackling low birthweight in newborns and based on current trajectories, the report estimates that 14.2% of newborns will have low birthweight in 2030. In the areas where the world has seen some headway – reducing child stunting and wasting, and increasing exclusive breastfeeding – the pace of progress is too slow to reach the global targets: globally 19.5% of children will be stunted and 6.2% of children will be wasted in 2030.

SOFI 2024 warns that two forms of malnutrition are on the rise: the micronutrient deficiency anaemia in women is increasing and is projected to reach 32.3% in 2030. New adult obesity data shows a decade of increase that sets the world on course to reach 1.2 billion adults living with obesity in 2030.

All of this is to say that more countries are off track than on track to achieve the 2030 global nutrition targets – the impacts of which will hinder generations and economies in the coming decades.

2.8 billion people, or one third of the world’s population, were unable to afford a healthy diet in 2022. This 2022 figure shows a continued two-year decline in the percentage and number of people who could not afford a healthy diet, returning to 2019 pre-pandemic levels. This is despite food prices increasing in 2022 and driving up the cost of a healthy diet globally and across all regions. Healthy diets are here defined as a diversity of safe and nutritious foods that deliver sufficient nutrients and energy for a healthy life.

Regionally, the number of people unable to afford a healthy diet in 2022 decreased in Asia (1.66 billion), Europe and North America (53.6 million) and Oceania (9.1 million) but increased on the African continent (924.8 million). This rise was most starkly seen in Sub-Saharan Africa where an additional 23.9 million people were unable to afford a healthy diet in 2022.

It is not yet possible to quantify the current financing available or the total amount needed to end hunger (SDG2.1) and malnutrition (SDG2.2). The report attributes this to the many different definitions of “financing for food security and nutrition” in use that creates a broad range of estimates and so puts forward the below definition for universal adoption to allow for a common approach to assessing financing:

Financing for food security and nutrition refers to the public and private financial resources, both domestic and foreign, that are directed towards eradicating hunger, food insecurity and all forms of malnutrition. They are targeted to ensure the availability, access, utilisation and stability of nutritious and safe foods, and practices that favour healthy diets, as well as health, education and social protection services that enable these, and include the financial resources that are directed towards strengthening the resilience of agrifood systems to the major drivers and underlying structural factors of hunger, food insecurity and malnutrition.

The report makes clear that current amounts of financing are insufficient to achieve SDG2.1 and SDG2.2 and that the financing gap between current levels of financing and the amount needed could be in the several trillions of dollars. Failing to fill this financing gap will see persistent hunger and malnutrition in 2030 – as detailed by the projections above – and risk economic, socio and environmental impacts that costs trillions of dollars.

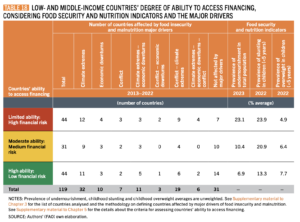

63% of low and middle-income countries have limited or moderate ability to access financing for food security and nutrition. This presents a serious hurdle to achieving SDG2.1 and SDG2.2 as new data in SOFI 2024 shows that the prevalence of undernourishment and child stunting is much higher in countries with limited access to financing. Additionally, countries with limited or moderate access to financing are often affected by one or more drivers (i.e. climate change, conflict etc.) of food insecurity and malnutrition. The table below illustrates the interplay between access to financing, countries affected by major drivers and their food security and nutrition status.

The report calls urgently for the scale up of innovative, equitable and inclusive financing solutions in countries with high levels of food insecurity and malnutrition and/or those affected by one or more major drivers. Official, public and private sources of financing should all be leveraged to reach countries with the greatest need for financing.

More on SOFI 2024

To learn more about the history of the SOFI report, the importance of financing to achieve impact on SDG2 and the lessons we can learn from countries that are seeing progress, listen to Future Fork’s In Conversation with Dr Maximo Torero, the Chief Economist of FAO, on Apple Podcasts or Spotify.

Join us in amplifying the findings of the 2024 report with this white label social media toolkit.