Since the beginning of the conflict in Ukraine two months ago, the world has witnessed unspeakable destruction and suffering, and the fastest-growing refugee crisis in Europe since the Second World War, with close to 8 million internally displaced people and millions more having fled the country. It has become clear that the war also has multiple implications for global markets and food security, in a time when the world is already battered by the Covid-19 pandemic and the increasingly devastating effects of climate change. In all this – aside of course from Ukraine – it has been developing countries, particularly in Africa and the Middle East, who have been the worst hit.

The Russian Federation and Ukraine are both important players in the global food market. Almost 50 countries rely on them for up to 30% of their import needs for wheat, and many of them on their import needs for fertilisers, too. The spike in fuel and energy prices, mostly due to market conditions, exacerbates the situation. Experts agree that these dimensions could lead to a major food crisis, or at the very least have severe impacts for food security and agriculture both in the short- and long-term.

The Chief Economist of the Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) Dr Máximo Torero, the Interim Director Agricultural Development at the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation Enock Chikava and Deputy President of AGRA Dr Fadel Ndiame, speaking at the May Networking Meeting hosted by the SDG2 Advocacy Hub, provided insights on these impacts – including opportunities for a shift towards more resilient and sustainable food systems.

Dr Maximo Torero

Dr Torero divided the risks of the Ukraine war into three categories: humanitarian (food availability and migration); macro (impacts on energy, debt, growth, exchange rates and nuclear contamination); and risks for food and agriculture. The latter manifest in terms of availability of input supplies such as seeds, feeds, pesticides and fertilisers; of impact on trade; and on logistics and infrastructure.

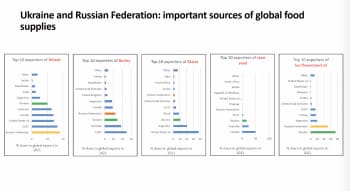

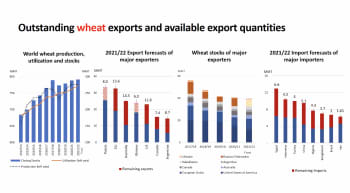

Both Russia and Ukraine rank amongst the top 10 exporters of wheat, barley, maize, rape seed and sunflowerseed oil globally. For wheat, the Russian Federation is the top exporter, closely followed by Ukraine in fifth place. The same applies to the export of fertilisers: globally, Russia is the top most important source of fertiliser supply. Lastly, Russia depends heavily on pesticide imports from the EU, adding a threat to the production of commodities in Russia next year.

This year, prices have already internalised the shocks, and their impact on food systems will hence not be as strong as they might be next year, should the situation continue or be exacerbated, clarified Dr Torero. Dividing scenarios into base, moderate and severe, the FAO predicts alarming spikes in malnutrition in the next two years: in a moderate scenario, the number of undernourished people would increase by 7.6 million and by up to 13.1 million in the severe one; if the export shortfalls continue and energy costs remain high, the number of undernourished people could rise by up to 11.2 million in a severe scenario. In all of this, Dr Torero stressed, the pressures affect first and foremost those countries that are already most vulnerable. Global nutrition leaders have been warning that the Ukraine crisis threatens to increase global malnutrition levels in mothers and children across low and lower middle-income contexts.

Dr Torero explained that fertiliser prices have risen due to the shortfalls in export from the Russian Federation. This affects those countries relying on fertiliser imports from Russia including in Africa and Latin America. One of the FAO’s core activities in this area is to identify the gaps in fertiliser production across the world, and to assess where the fertiliser stocks currently are and could be redistributed to. Although countries are looking for solutions and trying substitutes, we must face the reality that Russia currently holds most of the world’s fertiliser stocks. One part of the approach should be to find ways to move those fertilisers out of Russia to help reduce these risks.

In response to these challenges and to help low-income countries deal with the soaring prices, the FAO has put together six policy proposals. One that Dr Torero discussed is the Food Import Financing Facility (FIFF), which is aimed at easing immediate food import costs for food-importing low and lower middle-income countries while increasing global agricultural production and productivity in a sustainable way. The Facility asks eligible – mainly low and lower-middle-income countries – to commit to invest more in sustainable agrifood-systems and collects information that directly measures cost changes in food imports. Other FAO proposals aim at increasing the efficiency and types of social protection programmes and at reducing the wastage in fertilisers and foods.

Dr Fadel Ndiame

Dr Fadel Ndiame focused on the situation in Africa. In his work, Dr Ndiame matches economic opportunities available to smallholder farmers with effective agricultural investment programmes. Due to the African continent’s heavy reliance on food imports, Dr Ndiame said that rising food prices are already having an impact. We must recognise that the most important implication of this crisis is that it affects the ability of the most vulnerable to eat sufficient, nutritious food. In many African countries, strategic food reserves are starting to dwindle, and not nearly enough food is being produced to keep up with the demand. This demonstrates the urgent need to move to more resilient and diversified food systems on the continent.

Dr Ndiame however also highlighted the positives arising from this situation: some countries, for example Nigeria, have reacted by implementing emergency measures such as the blending of fertilisers. Others are ramping up their collection and analysis of data on food reserves and strive to establish more adequate food security strategies.

“This crisis calls for partnerships and the strengthening of cooperation platforms and issue-based coalitions such as the UN Food Systems Summit to achieve more sustainable food systems in the longer-term”

Enock Chikava

Finally, the group heard from Enock Chikava, who spoke about how smallholder farmers in particular are affected by the Ukraine crisis. We are faced not with one, but with a series of compounding crises and shocks. In most African economies, agriculture is a major contributor to GDP, (30% or more), and agriculture in those countries equals smallholder agriculture. In Sub-Saharan Africa for example, 60% of the entire population depend on smallholder agriculture for their livelihoods. This and the fact that the continent imports more than 35 billion dollars of food every year, it is evident that anything that affects agriculture will present a huge crisis – no matter where it originates. The question hence arises why Africa should be importing so much food in the first place. Such reliance on food imports, Mr Chikava stressed, is a symptom of a broken food system.

Smallholders require inputs and information. While Ukraine and Russia account for 30% of the world’s wheat exports, at the regional level 90% of all trade between the African continent and Russia is the trade of wheat. This shows that the impact of this crisis is deeply unequal. We must dissect, understand and take into account such data and evidence.

We must support the smallholders who are feeding the world and are on the frontlines of our food systems every day, and acknowledge that millions of people – their livelihoods, jobs and income – rely on the farming business. We need to ensure that Africa is not dependent on the import of one or a few commodities, Mr Chikava stressed, and we must encourage and incentivise ideas that can help this become a reality, including diversifying production, crops and diets.

What should we tell policy-makers?

Dr Ndiame urged governments to walk the talk: agriculture, he highlighted, requires public investment. Policies must be reprioritised and refocused towards providing effective support, through policies on capacity building, appropriate financing, accountability mechanisms, performance tracking etc. It is encouraging that several African countries have made progress in these areas, but we must do more to celebrate the culture of accountability and drive progress.

Mr Chikava’s final message was to look beyond the short-term: the food crisis might not reach critical levels this year, but we must not make the mistake of remaining inactive. Instead, we must think ahead to the next farming season, about fertiliser use efficiency and using all tools available today.

Dr Torero urged for caution on several dimensions: the gap in import bills especially for the most vulnerable countries could result in social unrest – something that must be avoided at all costs; and he seconded the importance of gaining efficiency in fertiliser use.

Conclusion

It is clearer than ever that good food is vulnerable to disruption. The three speakers issued clear calls to action to counter the trend towards a further rise in hunger and malnutrition, exacerbated by the war in Ukraine. At all costs, a mixing of crises resulting in social unrest and conflict elsewhere must be prevented. We must urgently support vulnerable countries especially in Africa in becoming less reliant on and diversifying their food imports, and in upscaling their own production of diverse and nutritious food. But first and foremost, smallholder farmers must be protected and supported.

At the end of the day, we are presented with an opportunity: an opportunity for Africa and other parts of the world to find ways to become more resilient.