A tall order for one, I know

I did a deep dive into rice farming practices in Malaysia. Rice is one of our staple foods and you would think that this would mean that our rice farmers live relatively comfortable lives. Not so. The majority of the rice-farming community in Malaysia is made up of smallholder subsistence farmers. Most fall into the “B40” category where the monthly median household income is under GBP 500.

Although rice is a subsidised good in Malaysia, the supply chain is convoluted, lacks transparency and government-run farm extension programmes are poorly executed, if they exist at all. Should the flow of money be taken as an accurate indicator of value, this particular chain would imply that rice farmers are the least important players. As chefs, you and I know this is far from the truth.

A bright spot in all of this is an increase in farmer-targeted initiatives currently focused on the indigenous rice-growing communities of East Malaysia.

Companies like Langit Collective provide a platform for these farmers to sell their top-notch agricultural products at fair prices that guarantee a living wage while providing training in data-driven regenerative farming techniques that combine indigenous methods with complementary SRI (System of Rice Intensification) and biodynamic practices.

The rice in this dish is grown by the Lun Bawang tribe in Long Semado Valley in Sarawak (East Malaysia), long-famed for their heirloom grain varieties and their traditional methods. Rice is an integral part of their cultural heritage and much of their lives revolves around growing it and growing it well.

They are their primary consumers and growing the best, tastiest rice is a point of pride.

The Lun Bawang people have incredibly discerning standards, having consumed only the best rice their whole lives. Seeds from exceptional (in terms of flavour and yield) harvests are kept and seed exchanges are common, ensuring biodiversity. The land is naturally fecund, a gift that is not exploited – as in more recent and widespread forms of agriculture.

Quite the opposite. Crop rotation is practiced on hilly paddy plots, while wet paddy fields are allowed to fallow for six months after being planted for twelve. In accordance with their traditions, water buffalo graze on the leftover rice stalks on these fallowed fields, contributing to the natural fertilisation and regeneration of the soil. We (big “We”) are the grateful beneficiaries of their accrued agricultural wisdom.

Rice is more than a conveniently marketable source of income for the Lun Bawang tribe. It is identity, it is culture, it is community. It is a way of life that has existed for generations; the evidence of which we now have the privilege of experiencing, in a small but completely tangible way.

The Lun Bawang people have thoughtfully cultivated a vibrant, sophisticated and all-encompassing ecosystem that celebrates their dynamic rice-growing culture. With this understanding, it became evident that making a dish that sustained the beautiful, but singular note of ‘rice’ would not do justice to the complexity of the entire score. Instead, this dish aspires to respect the holism of the Lun Bawang tribe’s relationship with rice-growing.

One that lifts diversity over homogeneity, stewardship over ownership, and generativity over reductivism.

Nasi Lun Bawang Notes

I must preface this by saying that one tiny dessert could not possibly claim to speak to the deep, nuanced Lun Bawang culture. That is not the intention.

This dessert was, personally, a way of respecting and understanding the limitations of the nature of crafting narratives through food. Cultural authenticity is a fraught and sticky subject. I am navigating that by trying to honour the root of the guiding wisdom and thought, not by attempting to directly replicate or reproduce. I am learning that it is important to at least create a framework (a delicious one) that does not detract from the “reality of the force of the thing” or its complexity.

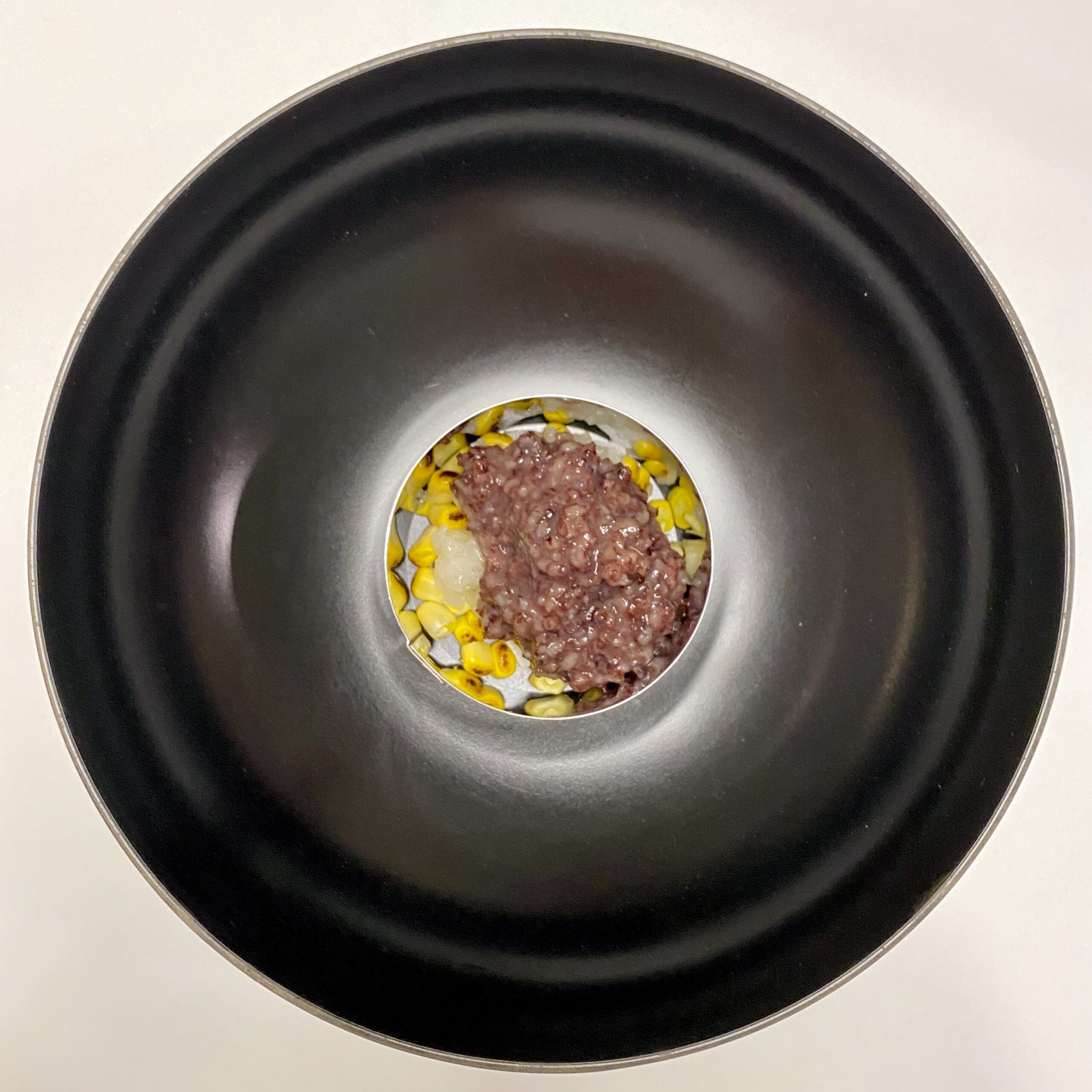

Spotlighting one superstar ingredient (rice) that comes out of a web of relationships of people, place and time didn’t feel right to me. Instead, I wanted to present, alongside the rice, some ingredients that reflect the everyday joys of Lun Bawang cuisine. It was a fun challenge to create a dish where the ingredient list dictated all the techniques; finding methods that best allowed less-obvious flavour and texture combinations to complement and play off each other.

Some notes on the ingredients used in the dessert and their context in the Lun Bawang ecosystem:

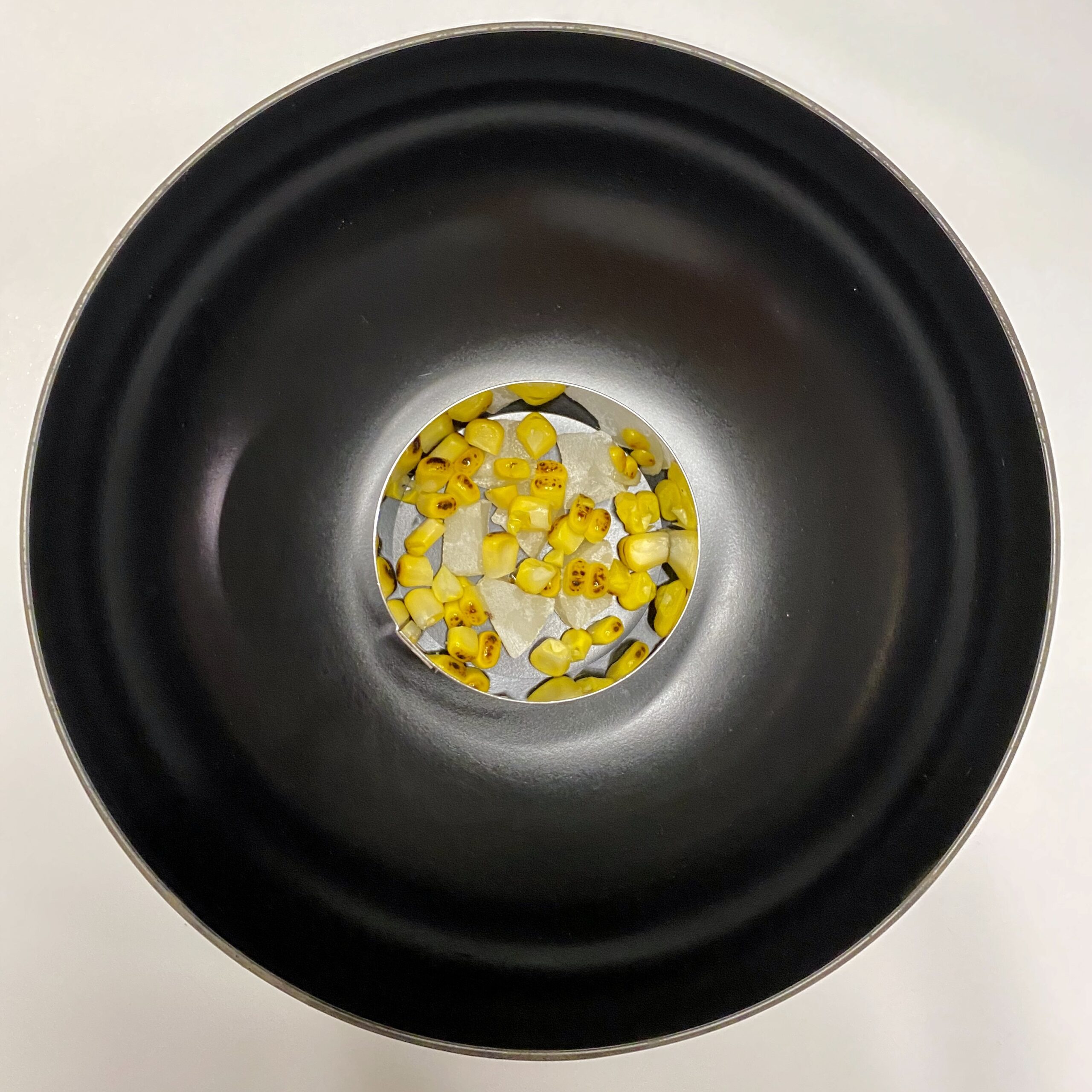

Corn

A Lun Bawang staple food, grown with rice and millet and Job’s tears. The community has over 30 heirloom grain varieties in their seed banks.

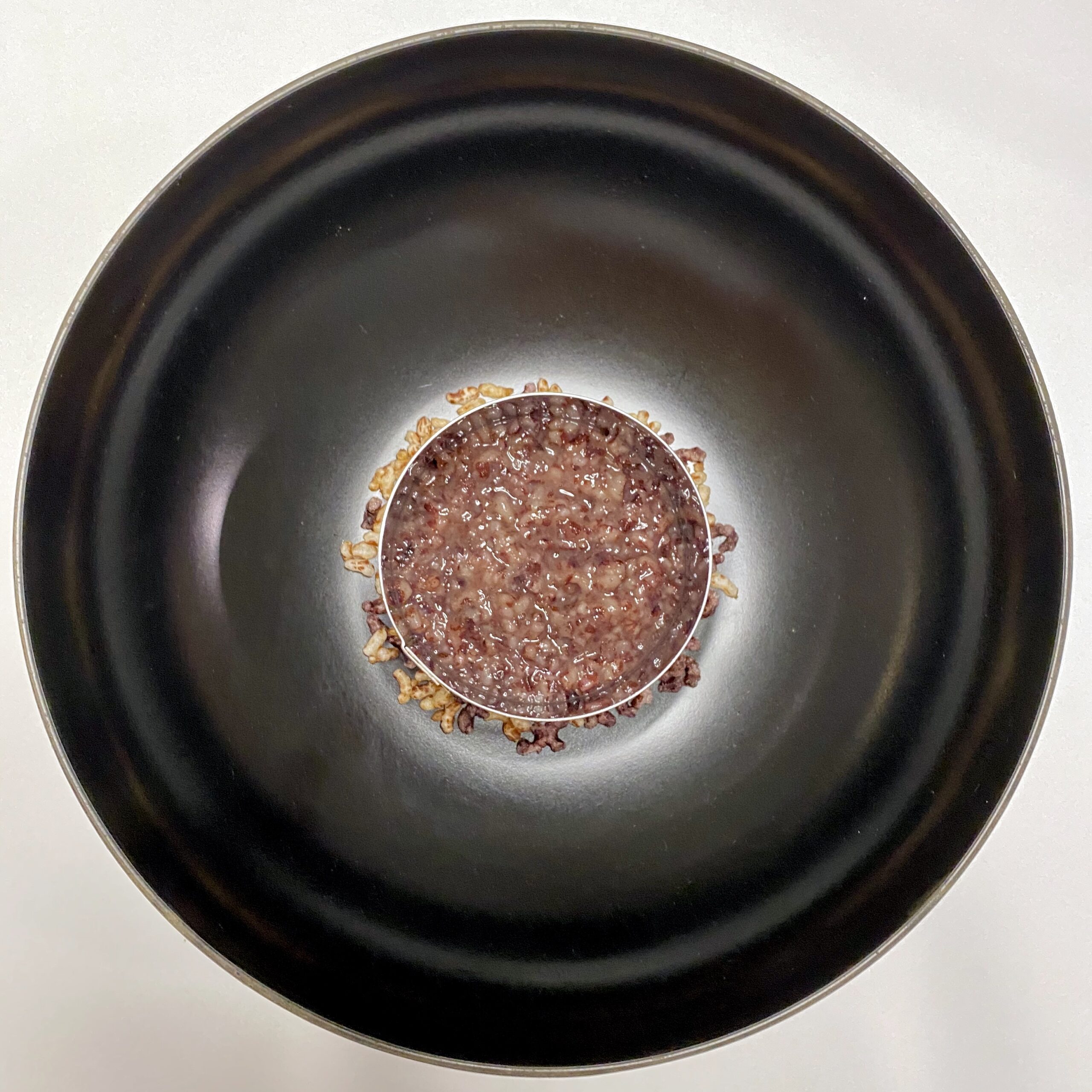

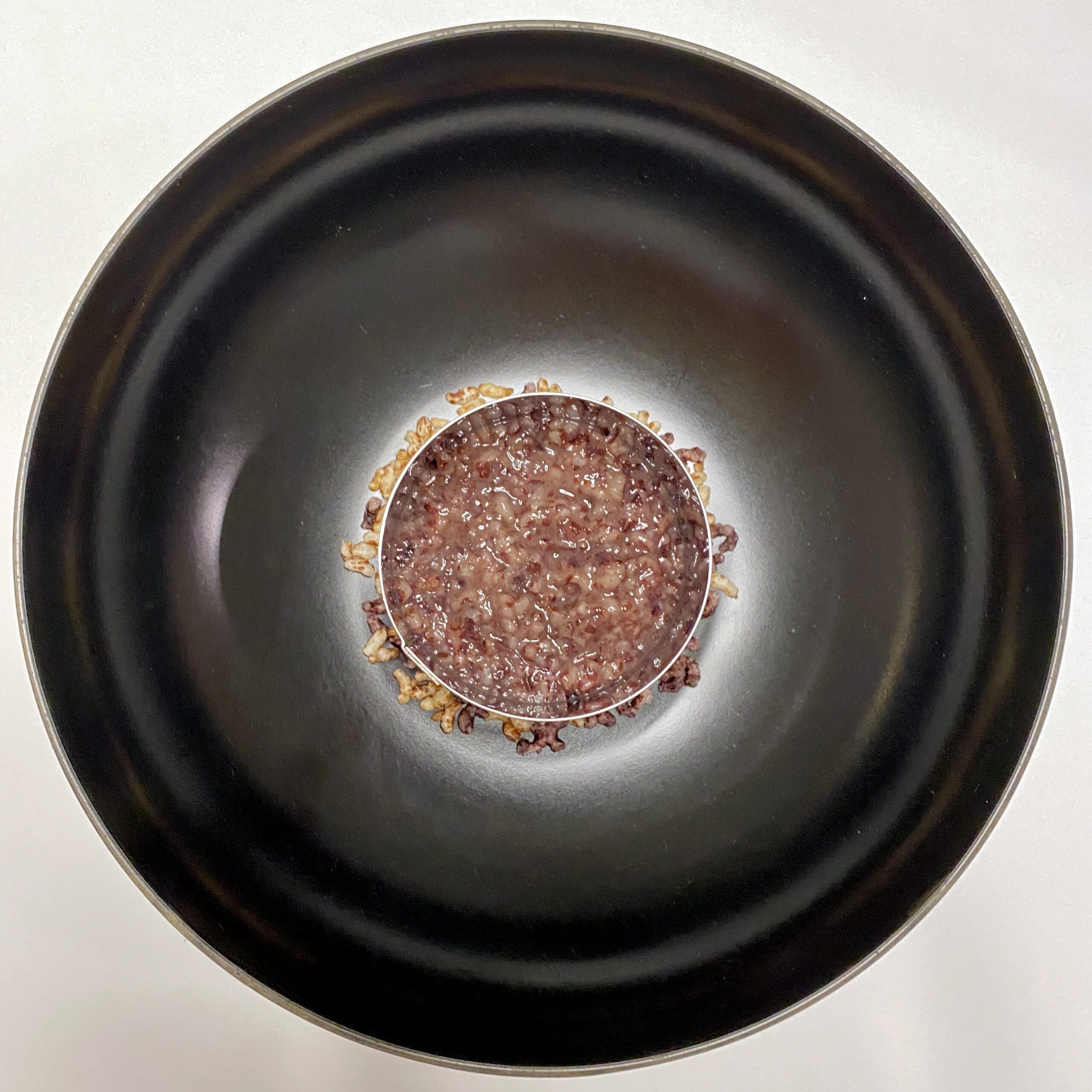

Rice coffee

A Ba’kelalan specialty (Ba’kelalan is an area of nine Lun Bawang villages). It is made by heavily roasting rice in a pan and steeping it in hot water.

Tapai

Refers to both a drink and a dessert of fermented rice, common in many parts of Southeast Asia, including East and Peninsular Malaysia. It is an important part of many traditional celebrations. It is made with a starter called ragi, which you can think of as the koji to amazake.

Gula Apong

A natural sweetener made from the sap of Nipah Palms that grow in swampy marshlands along the coastlines of Sarawak. It is the main sweetener used in this dessert.

Foraged herbs and leaves

These are commonly used to flavour and wrap everyday meals. Pandan flavours the rice porridge. Banana leaves are used in the cooking of the glutinous rice for the ‘mochi’ and to wrap the blistered corn. A candied Daun Kaduk tops the dish.

Nasi Lun Bawang Recipes

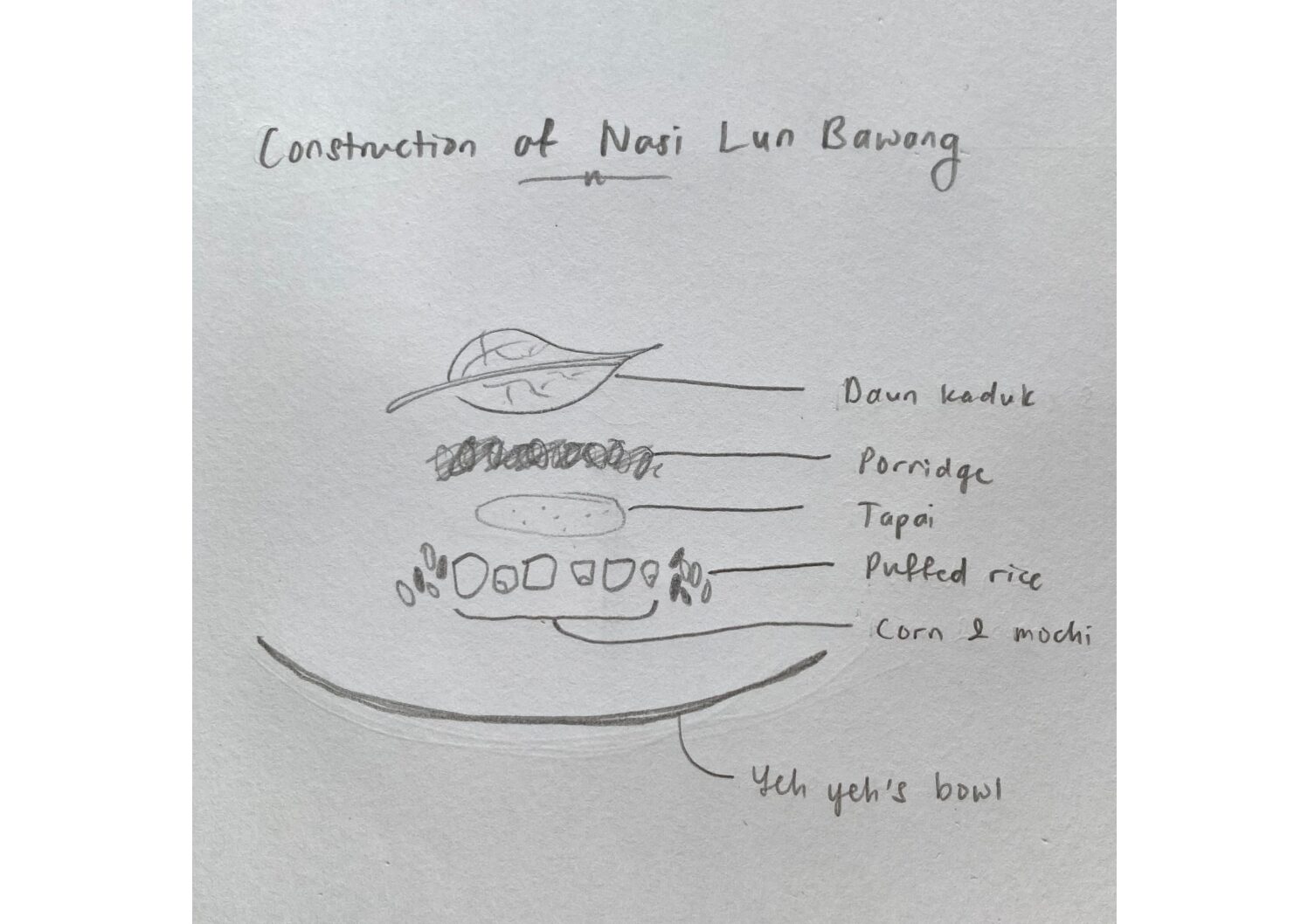

When constructing this dessert, I imagined it as a ‘bridge’ dish – right between the end of all savoury courses and the first sweet course of a tasting menu.

It gives an overall impression of sweetness, but has several more savoury flavour components to anchor that sweetness.

I include some notes on my thought processes as well as tasting notes. Find the recipes below!