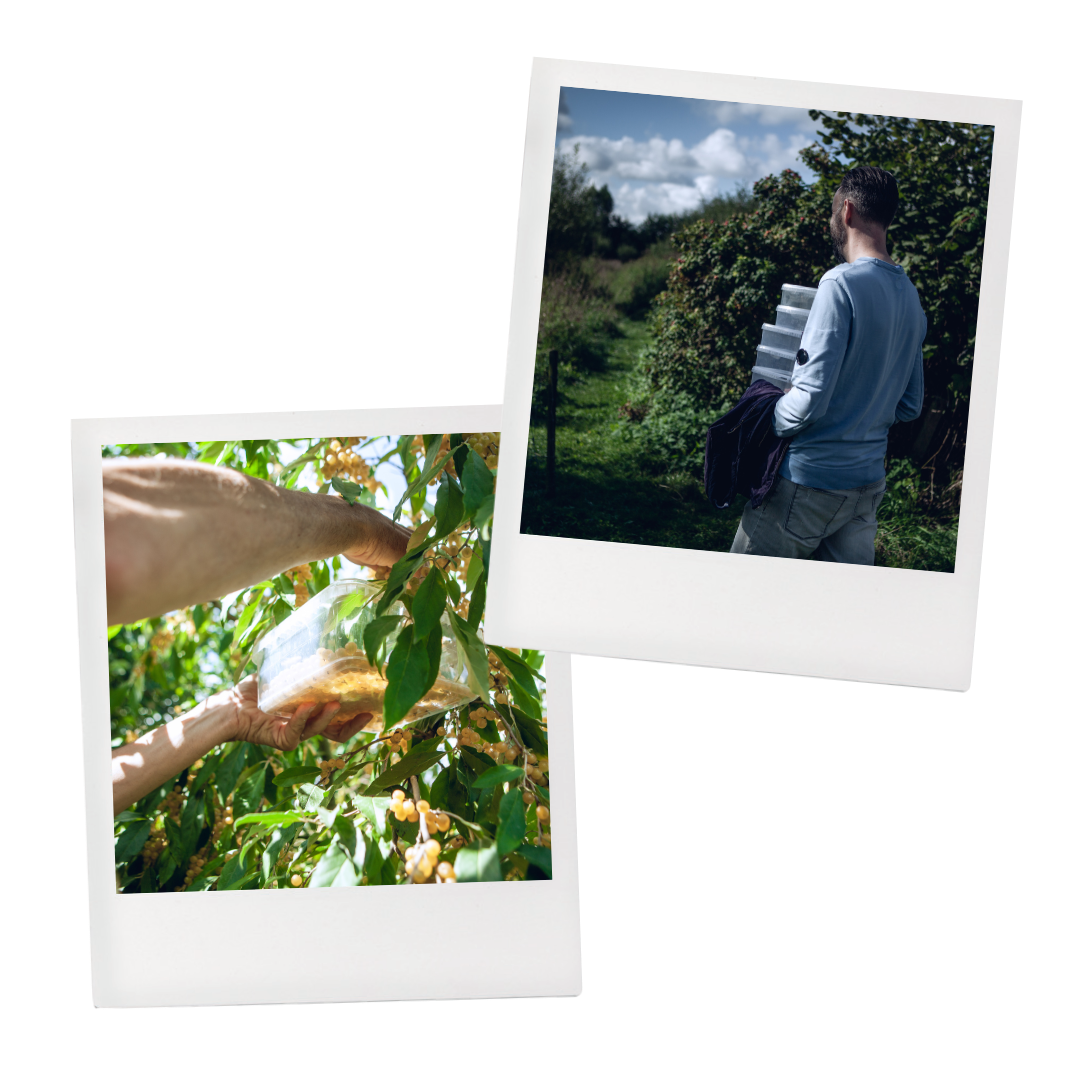

If you’re looking for Michelin-starred Chef Emile van der Staak, start by going to the six-acre food forest that has become the foundation of his kitchen. You’ll likely find him tasting, foraging, and studying the rhythms of a landscape that produces food without plows or pesticides.

Eight miles from the Ketelbroek Food Forest is his award-winning restaurant in Nijmegen, De Nieuwe Winkel, where Chef Emile van der Staak is pioneering botanical gastronomy.

At De Nieuwe Winkel, Chef Emile and his team craft menus that celebrate biodiversity and the boundless potential of plants, reimagining a vision of sustainable cuisine. From Chinese mahogany to chestnut “chocolate”, forgotten herbs and wild edibles become teachers, inviting us to honour and get inspired by nature.

He sees food forests as a blueprint for the future—an approach to agriculture that builds resilience and long-term stewardship.

For him, the role of a chef is one of moral ambition, and one that challenges us to stay curious, to experiment, and to plant seeds that grow beyond our time.

We asked him how food forests, seasonality, and a deep respect for nature have shaped his cuisine, his philosophy, and his vision for the future of food.

Your culinary approach at De Nieuwe Winkel is rooted in botanical gastronomy. Can you tell us a bit about your food philosophy?

At De Nieuwe Winkel, our culinary philosophy revolves around botanical gastronomy, which means that plants take center stage in everything we do. We work closely with local growers, foragers, and scientists to explore the incredible potential of plants, using them in innovative ways to create deep, layered flavours. Our focus is not just on using plants as substitutes for meat but on truly celebrating their unique qualities. Ultimately, our goal is to redefine fine dining with plants, proving that botanical gastronomy can be just as indulgent, complex, and satisfying as the 18th-century recipes that have shaped traditional haute cuisine.

You’ve credited Wouter van Eck, the founder of the Ketelbroek Food Forest, with teaching you about food forests and their role in shaping a better food future. How do you see food forests contributing to sustainable and equitable food systems, from safeguarding biodiversity to supporting livelihoods?

Wouter van Eck has been instrumental in shaping my understanding of food forests and their potential to transform our food system. Food forests offer a radically different way of thinking about agriculture—one that works with nature rather than against it. Instead of monocultures that deplete the soil and require constant external inputs, food forests are self-sustaining ecosystems that mimic natural forests, providing food while enhancing biodiversity.

At De Nieuwe Winkel, we see food forests as a blueprint for the future—a way to create a truly sustainable and delicious food system that nourishes both people and the planet.

How did your collaboration with the Ketelbroek Food Forest come about and how does it impact your menu?

Over ten years ago, it actually took a mutual friend from Amsterdam to connect me with Wouter. At first, I wasn’t too eager to go—especially not on that particular day. It was a rainy, cold November afternoon, and the idea of trudging through a muddy field didn’t sound appealing.

But when I arrived and met Wouter for the first time, everything changed with his very first sentence:

“Agriculture as we know it means an empty field in spring, then a lot of input—big machines, fossil fuel, pesticides, fertilisers, weeding, watering, plowing—and at the end of the season, it’s an empty field again. This is not how nature works.”

Since that day, the Ketelbroek Food Forest has become the foundation of our kitchen at De Nieuwe Winkel. It provides us with ingredients that simply don’t exist in conventional agriculture—perennial vegetables, forgotten herbs, nuts, berries, and edible leaves that bring entirely new flavours and textures to our dishes. These ingredients challenge us to rethink how we cook, pushing us to develop new techniques and rediscover old ones.

You work with so many diverse perennial plants. Are there any ingredients you discovered that surprised you?

One of the most exciting things about working with a food forest is that it constantly challenges and surprises me. Chinese mahogany is one of those discoveries that completely changed how I think about flavour. The young leaves have an intense aroma, almost like roasted onion or fried garlic, which makes them an incredible addition to our dishes. Japanese ginger is another favorite—the young shoots and flower buds have this wonderfully bright, citrusy spice that pairs beautifully with fermented ingredients. Then there’s bamboo, which gives us tender, crisp shoots in the spring, Mongolian lemons, tiny citrus fruits that pack an unexpected punch of acidity, and Sichuan pepperberry, which adds an electrifying, numbing heat that transforms both sweet and savory dishes.

What are some of your favourite dishes that you’ve created from ingredients sourced from the food forest?

One of my favorite dishes we’ve created is a broth infused with the wood of Chinese mahogany, which brings a deep umami complexity without needing traditional aromatics. Another is a dish where the young bamboo shoots, lightly grilled and dressed with a sauce made from their own ferment, have been a revelation. And the Sichuan pepperberry has found its way into both desserts and savory dishes, bringing an unexpected tingling sensation that enhances other flavours in a completely unique way.

You also have a food technologist on your team to help explore new applications for ingredients, and play with the senses to create delicious and unexpected gastronomic experiences.

What are some of the most exciting or unconventional techniques you’ve developed to highlight these ingredients?

One example is how we use SCOBY, the symbiotic culture of bacteria and yeast typically used to ferment kombucha. Instead of using it just for its fermentation properties, we explore its unique texture.

Another exciting project has been creating chocolate without cacao beans. With climate change threatening traditional cacao-growing regions, we started thinking: what if we could achieve the same deep, complex flavours using local ingredients? We experimented with chestnuts and found that, when fermented and processed correctly, they develop notes strikingly similar to cacao. The result is a rich, deep-flavoured “chocolate” made entirely from ingredients that grow in our region.

We also play a lot with molds and yeast to create unexpected flavours. Some strains of mold can generate citrusy compounds, meaning we can produce lemon-like flavours without using actual lemons. Similarly, by carefully controlling fermentation conditions, we’ve been able to develop aromas reminiscent of tropical fruit—a way to bring exotic flavours into our kitchen without relying on imported ingredients.

What have been some of the greatest challenges in this process? What inspires you to keep pushing?

One of the greatest challenges in this process is that there is no blueprint. Botanical gastronomy is still uncharted territory in many ways, so we’re constantly experimenting, failing, learning, and refining. It’s a slow, iterative process that requires patience and persistence.

Richard Sennett’s insights on craftsmanship resonate deeply with me. A true craftsman is never satisfied—there’s always a way to make something better, to refine a technique, to push an idea further. That mindset drives us in the kitchen every day. It’s not about chasing perfection, but about committing to continuous improvement, always looking for the next step, the next discovery.

At the same time, I see our work through the lens of moral ambition—the idea that progress isn’t just about innovation or creativity, but about doing what’s right. The way we eat has a profound impact on the world, and I believe that chefs have a responsibility to rethink our relationship with food. How can we create something that is both deeply satisfying and truly sustainable? How can we honor nature rather than exploit it?

That’s what keeps me going. The excitement of discovering a new flavour hidden in a plant that no one has looked at before.

What’s on the horizon for you? Is there one plant that you’re curious about and hoping to experiment with, or something you’re looking forward to as the seasons change?

There’s always something new to explore, but if I had to pick one plant that fascinates me right now, it would be the Korean Pine (Pinus koraiensis ‘Silveray’). It’s a slow-growing tree that produces some of the biggest and most flavourful pine nuts you can find—but only after about 40 years. That timescale is humbling. It forces you to think beyond seasons, beyond menus, beyond your own lifetime. But what’s even more incredible is that once it starts producing, it can continue to give harvests for over 1,200 years.

It’s a reminder that the best things often take time, and that our role as chefs isn’t just about working with what’s available now, but also about planting seeds—both literally and metaphorically—for the future.

“My advice to young chefs who want to be part of advocating for change is simple: stay curious, stay patient, and stay stubborn. Change doesn’t happen because one person makes a grand gesture. It happens when many people make small, meaningful choices every single day. So start where you are, use what you have, and cook like the future depends on it—because it does.“

About Chef Emile van der Staak

Michelin-star chef Emile van der Staak is helping to inspire a better food future. A champion of agroecology, biodiversity and botanical gastronomy, his food tells the story of plant magic. Coupling curiosity and a deep commitment to making an impact, he’s charting a new path for haute cuisine to reimagine how we connect with nature from food forests to the fork.

His MICHELIN Green Star restaurant in the Netherlands, De Nieuwe Winkel, was elected the world’s best vegetable restaurant in 2023. In 2024, Emile was Gault&Milau Netherlands’ chef of the year.

About Restaurant De Nieuwe Winkel

We could well trust nature a bit more.

We experiment. We create, explore and have fun. We discover and fail. We only cook with plants. In fact, we believe in botanical gastronomy. You eat what we find nearby. In food forests, in natural fields and in gardens. Be surprised. Taste the region. Taste the season.

We are all slowly depleting the earth. Our current consumption pattern is not sustainable, but finite. Moreover, our menu defines the landscape. Just look at the endless fields of ryegrass, mangold and field corn: all this is to produce fodder or hay for dairy cows. We can do things differently.

At De Nieuwe Winkel, we cook to make the world a better place. That’s why we use plants: botanical gastronomy. We look for applications for edible plants. These can be plants that have grown here for centuries, but also plants from further afield. Japanese ginger, Chinese mahogany and honeyberries from Siberia, for instance, feel surprisingly at home in the Netherlands.

Once nature has done its work, it is our turn. We pick. Smell. Taste. Analyse. Ferment. Cook. Until there is something on your plate that amazes and overwhelms you.

Learn more at denieuwewinkel.com.